“I don’t think there’s anything to see here—maybe we should turn back.” Stephanie and I had driven northwest from the city of Zadar on Croatia’s northern coast and crossed the bridge to Pag Island. The sun was shining, the sea a stunningly deep blue, but on both sides of the road, all we could see for miles was a rocky, treeless landscape. Hardly any vegetation and no houses. Who would want to live in this harsh landscape?

Stephanie reminded me that Pag Island was famous for two things—cheese and lace-making. We had seen exquisite examples of the lace a week earlier on a visit to the Ethnographic Museum in Croatia’s capital, Zagreb. If there was cheese and lace, then there had to be people. We kept driving.

Pag is the fifth largest island off the Croatian coast, and has the longest coastline. It stretches 37 miles southeast to northwest; at its widest, it’s only six miles, at its narrowest just over one mile.

According to the Lonely Planet Guide, Pag has two places worth visiting. Novalja is a party town, its nearby Zrće beach lined with nightclubs and bars where the music and dancing go on way past the wee hours. Because it’s a long time since Stephanie and I were anywhere near the age of 30, we opted for the more sedate but historically interesting destination of Pag Town. As we approached, we passed pools where sea water is dammed, and the water left to evaporate to yield sea salt.

According to written records, salt has been produced in shallow coves around the bay for more than a thousand years, but the industry could be even older, dating from Roman times. From the 12th to the 14th centuries, the Venetian Empire and the rulers of Croatia and Hungary fought for control of Pag and other islands. Salt was valued not only as a seasoning but because if its ability to preserve food, so its manufacture and export became a lucrative business. In the early 15th century, as Pag’s population grew, its Venetian rulers hired the prominent architect Juraj Dalmatinac to design a new town with a central square, a cathedral, castle, palaces for the duke and bishop, and fortified walls. After Venice lost its independence in 1797, Austria-Hungary and France fought for control of the coastal region with victory going to the Austrians.

At the height of the industry, Pag had nine salt warehouses. One of the remaining ones houses the salt museum. It was a Sunday and early in the tourist season. We were the only visitors, so the friendly guide gave us a personal tour. We said we had not appreciated how important the industry was. “For the Venetians, salt was more valuable than gold,” he told us.

The basic process of salt extraction has not changed much over the centuries, Sea water is channeled into shallow pools which are closed off. Over time, exposed to the sun and wind, the water evaporates, and the salt begins to crystallize and settle.

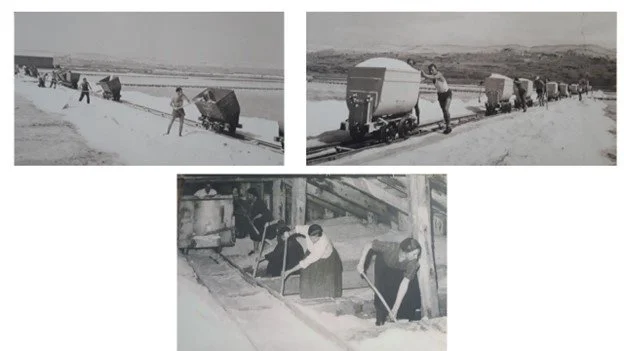

The museum displays the tools, carts and rail cars used to collect the crystallized salt. Photographs from the early 20th century show bare-chested young men shoveling it into the cars and pushing them to warehouses where women shoveled the salt into holding bins. The annual salt harvest was hot, exhausting work. Today, machines do most of the hard labor.

We asked the guide where we could buy the famous Pag sheep’s milk cheese, Paški sir, generally regarded as the most famous of all artisan cheeses in Croatia. It owes its distinctive flavor to the topography and climate of the region. In winter, a strong, cool, dry wind from the coastal mountain range picks up salt water and scatters a white salty dust across the rocky hills. The salt dust becomes wet when it falls onto vegetation. In these conditions, only the extremely resilient plant species survive. Pag's sheep graze freely, giving their milk a distinctive salty taste that is preserved in the cheese.

“It’s Sunday and the shops are closed, but you could try to find Teresa. She makes her own cheese.”

He gave us directions to an apartment block close to the museum. We wandered around for a few minutes before I walked into the courtyard and called out Teresa’s name. She appeared from the back door of her apartment, and welcomed us into the kitchen where she makes the cheese. The one we selected survived the rest of the three-week trip and two customs inspections, and is now slowly aging on our kitchen counter. It’s likely the only Paški sir in Charleston, West Virginia.