“The parking in Rovinj is a nightmare.” Our host at the bed-and-breakfast at a village in the center of the Istrian peninsula advised us to leave early for the ancient, picturesque Adriatic port. “They don’t allow cars in the Old Town, so try the Valdibora by the harbor.”

We stopped at Velika (Big) Valdibora, the closest lot to the Old Town, only to find a “reserved for residents” sign. We circled Mala (Small) Valdibora until we found a spot. The next task was figuring out how to pay for parking. Since arriving in Croatia a week earlier, we’d negotiated different systems. Some machines wanted coins and bills, others a credit card. Some printed a ticket; on others, you entered your registration plate on a keypad. The instructions were in Croatian, so if we could not figure them out, we stood by the machine looking foreign and forlorn until a passer-by stopped to help us.

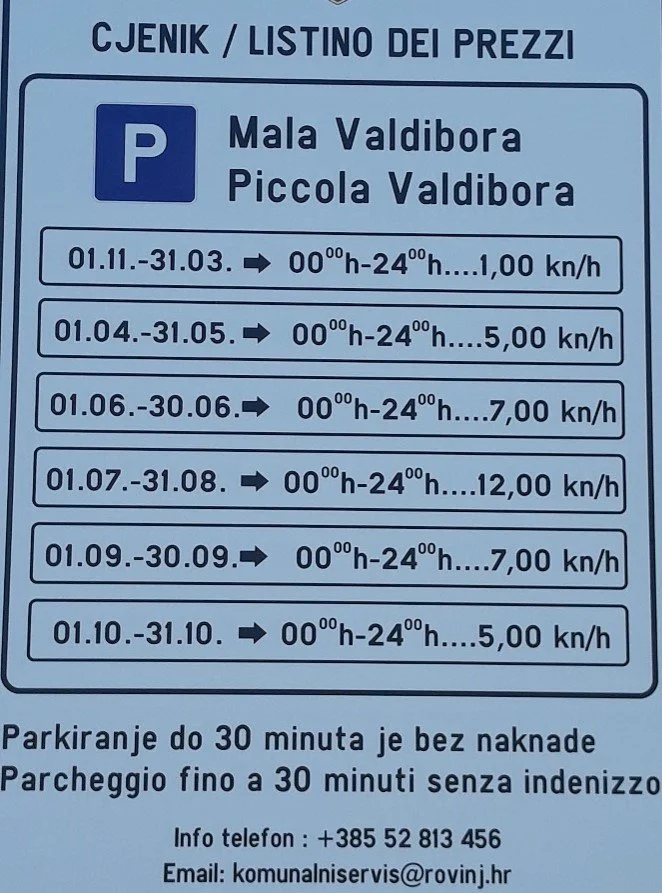

The parking sign at Mala Valdibora provided a seasonal tariff, making us glad we were there in May for 5 kuna ($0.70) per hour), rather than in July or August (12 kuna). Just in case we had trouble reading the Croatian, the Piccola Valdibora sign was also in Italian.

“There’s something particularly romantic about Rovinj—the most Italian town in Croatia’s most Italian region,” writes Rick Steves. “Rovinj’s streets are delightfully twisty, its ancient houses are characteristically crumbling, and its harbor—lively with real-life fisherman—is a as salty as they come. Like a little Venice on a hill, Rovinj is the atmospheric setting of your Croatian seaside dreams.”

Steves is gushing a little (and I would certainly have remembered if I had had any Croatian seaside dreams) but he’s right about the Italian influence. Looking at the map of northwestern Croatia and Istria, the wedge-shaped peninsula jutting into the Adriatic, it’s not surprising that for some people in this region Italian is their second, or sometimes first, language. Rovinj (Rovigno in Italian), perched on a narrow isthmus, is just a 90-minute drive from Trieste, Italy’s deep-water commercial port at the north end of the Adriatic, and three hours from Venice. The road south crosses the small sliver of coastal Slovenia. Our host at the B & B, which specializes in farm-to-table Istrian cuisine, told us Italian visitors often pop down for a weekend getaway or even an evening meal.

From Roman times, Rovinj, originally an island, was an important fishing and trading port in the northern Adriatic. In 1199, its leaders signed a pact with the powerful republic of Dubrovnik to protect its shipping trade from pirates. From the 13th century it fell under the control of the other regional sea power, the Venetians, who built city walls and sea defenses. With its population growing as immigrants fled Ottoman invasions, Rovinj had to expand beyond the island. In 1763, the narrow channel separating the town from the mainland was filled in and the old town became a peninsula.

For more than a century after the fall of Venice in 1797, Istria was under Austrian rule, except for French occupation during the Napoleonic Wars. After the Austro-Hungarian Empire was broken up after World War I, the peninsula was ceded to Italy which had fought on the Allied side. Immigrants from Mussolini’s Italy arrived and many Croats, fearing fascism, left. After Italy’s defeat in World War II, Istria became part of Yugoslavia and the Italians departed, fearing Tito’s communism.

Five centuries of Venetian rule left a lasting mark on Rovinj. On its architecture—the landmark Baroque church of St. Euphemia on top of the hill with its imposing bell tower, modelled on the campanile of St. Mark’s in Venice, the four-story merchants’ houses on the waterfront, the cobblestone alleys, the tiny squares and courtyards. On its cuisine--every restaurant serves pasta dishes, often with truffles or Istrian air-cured ham. And on its language--both Croatian and Italian are official languages, are used on signs and are taught in schools. Locals slip easily between the two, sometimes in the same sentence.

Istrians have learned to stoically accept their messy history where control of the region has passed from one super-power to another. Steves quotes a twentysomething in Rovinj: “My ancestors lived in Venice. My great-grandfather lived in Austria. My grandfather lived in Italy. My father lived in Yugoslavia. I live in Croatia. My son will live in the European Union. And we’ve all lived in the same town.”