For many Albanians, all roads lead to a large parking lot surrounded by concrete apartment blocks and commercial high rises in the northern suburbs of the capital, Tirana.

By most macro-economic measures, Albania is still the third poorest country in Europe (after Ukraine and Moldova) and by a small margin the poorest in the West Balkans. According to 2021 statistics from the transport ministry, it has the lowest car ownership rate in Europe, with just one in five citizens owning a vehicle.

Those numbers need to be taken with a large pinch of salt—or maybe a shot of Albanian raki—because Albanians are famously distrustful of government and sometimes experience temporary memory loss when personal property taxes are involved. But even if the growing economy has boosted car ownership, it’s still not an option for the working and lower middle class. They take the bus.

Stephanie and I joined them on our trip north to Shkoder, the commercial and cultural capital of northern Albania, and then, three days later, to Berat, the breathtakingly beautiful “city of a thousand windows” with a medieval fortress in the Tomorri mountain range south of the capital.

It’s a 30-minute (depending on traffic) $10 cab ride from central Tirana to the prosaically named North/South (Veri/Jug) bus terminal just off the airport road, across the roundabout from the Casa Italia shopping center and the Waikiki Outlet Mall. Calling it a “terminal” is an overstatement. It’s just a large asphalt parking lot with coaches and minibuses lined up on two sides—northern destinations to the left, southern to the right. The facilities are, well, lacking. There are no sheltered areas and no seats. When we asked for directions to the toilet, a driver guided us to a gap in the hedge that lines one side of the lot and pointed us to a café a short block away.

As far as we could tell, all long-distance buses are run by private operators. There are no bus company logos, so we assume most are small operations—maybe just one bus with the driver and conductor, run as a family business. It may sound chaotic, but it’s a very efficient system. All buses have their destination posted in the windshield.

As the Bradt travel guide notes, the “common denominator is that they run to timetables.” Outside the North/South station, the schedules are posted on boards, with the earliest buses leaving at 5:30 or 6:00 a.m., especially for destinations in the far south or western Kosovo.

The three buses we’ve taken so far—to Shkoder and back, and from Tirana to Berat—were comfortable, air-conditioned and left right on time. Arrival time is more iffy—partly because of traffic but also because the buses pick up and drop off passengers along the route, sometimes in a town or village, sometimes at a gas station or café. They also operate an informal package delivery service. As we waited for the Shkoder bus to depart, cars and motorcycles rolled up and handed over packages to the conductor who stashed them in the luggage compartment to be picked up on arrival.

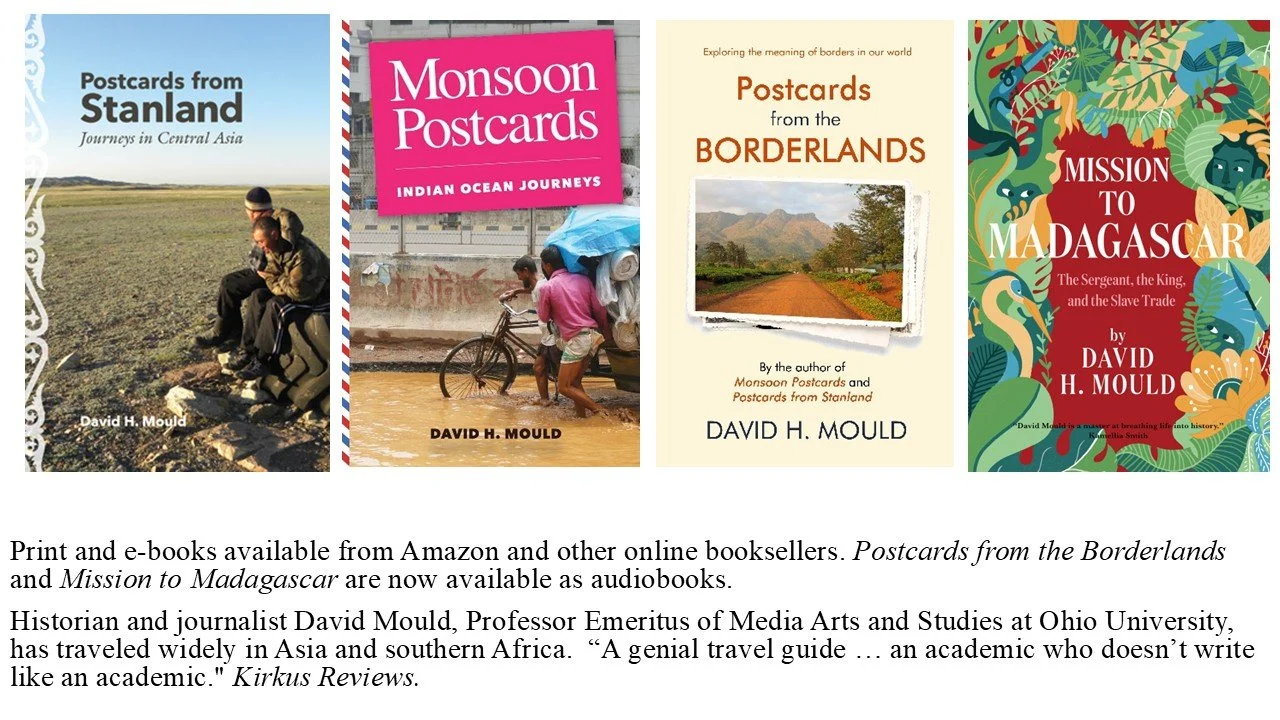

Stephanie at the Shkoder bus

It's not only an efficient system but (at least for us) an inexpensive one. It’s about 75 miles from Tirana to Shkoder, about 90 to Berat. The fare was 500 lek (just over $5) for a 2-2/12 hour trip. That’s a total of 1,000 lek, which is what we paid for the cab from central Tirana to the bus station.