When I was growing up in Britain in the 1950s and 1960s, a shilling was worth something. To be precise, there were 20 shillings to the British pound, back in the days when one pound—yes, just one pound-- bought you a good three-course lunch. At elementary school, our multiplication tables included what now seem to be arcane calculations—12 pennies to the shilling, 20 shillings to the pound, and 21 shillings to something called a guinea, the unit of prize money for jockeys winning horse races and men in red suits on horses with dogs chasing foxes and other everyday sporting activities. When I started my first job as a trainee newspaper reporter, my weekly salary was 15 pounds, ten shillings and sixpence. I was pretty broke most of the time but could still pay for rent, food and a round of pints at the pub. A few shillings went a long way. Then in the early 1970s, Britain moved to a decimal currency and we all forgot about shillings.

But I digress from the Tanzanian shilling, which I’ve been coping with on my first day in Tanzania’s capital, Dar es Salaam (I’m here to work on a UNICEF research project). Tanzania consists of the former Tanganyika, handed over by the Germans to the British under the Versailles Treaty that ended World War I, and the former British protectorate of Zanzibar, the two countries uniting in 1964. Tanzania may have gotten rid of the British, but it retained the shilling as its currency. Technically, the Tanzanian shilling is the offspring of the East African shilling, the currency of Britain’s East African colonies until they gained independence in the 1960s. In East Africa, as in Britain, there were 20 shillings to the pound, but schoolchildren were saved from the 12 times table because the shilling was divided into 100 cents. Tanzania, presumably hoping to enjoy an economic boom and to have a stable currency, dropped the pound, so today it’s just the shilling, divided into 100 cents (semi in Kiswahili).

The problem is that the shilling does not buy much anymore. The official rate of exchange is close to 2,500 shillings to the dollar. My auto-rickshaw ride back from the harbor area cost 10,000. Cappuccino and cake in a restaurant 15,000. The prosaically named CBD (Commercial Business District) Hotel on Nkrumah Street is a bargain at 160,000 per night, including the eclectic breakfast buffet featuring British, Indian and Chinese dishes.

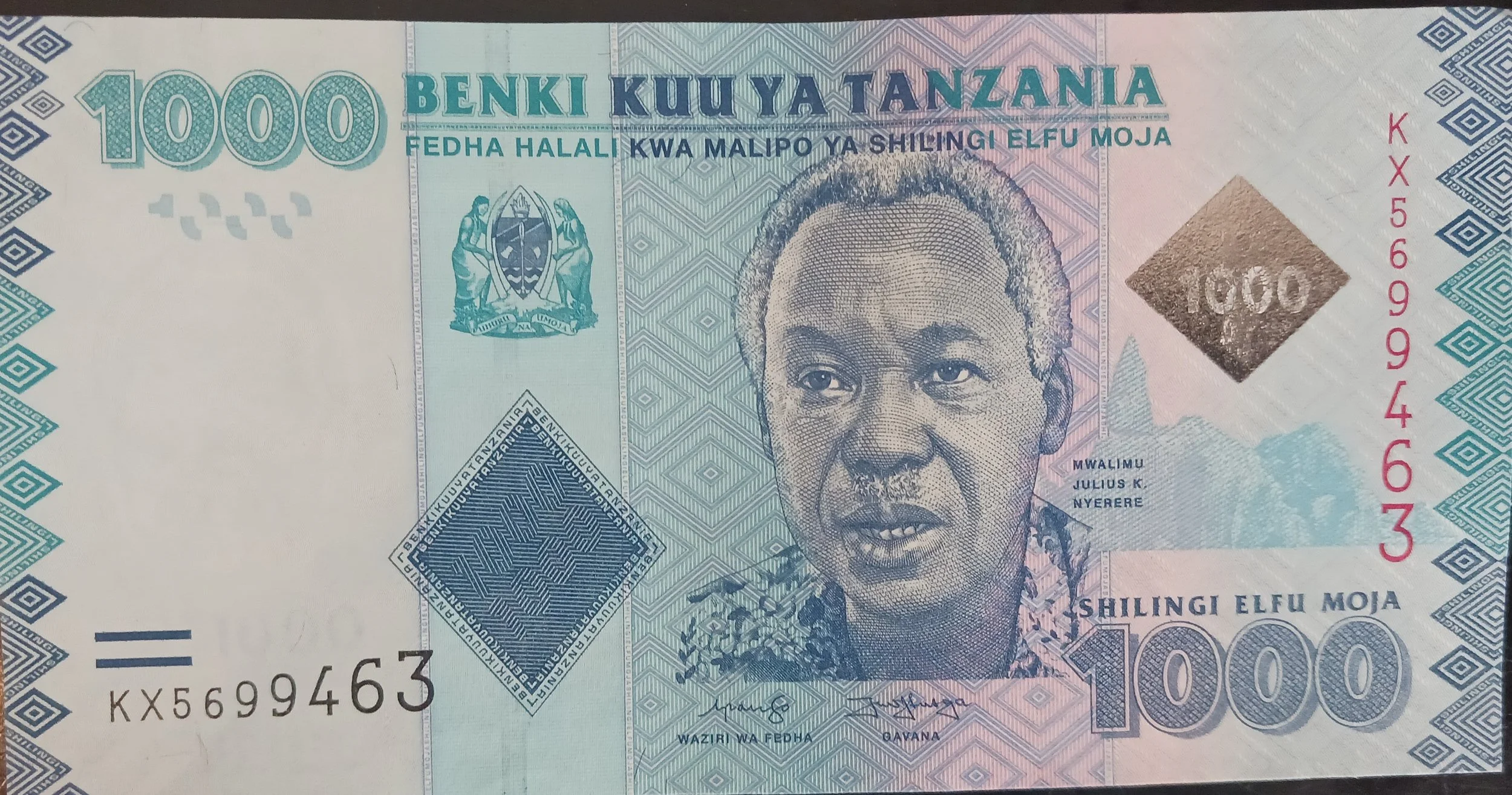

I’m no central banker, but you’d think they could just drop a couple of zeros to make calculations simpler. There’s no sign of that happening, and the problem is compounded by the fact that the largest bill in circulation is the 10,000 (worth about $4). Yes, life is cheaper in Tanzania, but it’s not that cheap. Today, I withdrew 300,000 shillings from the ATM and it came in a large stack—10,000, 5,000, 2,000 and 1,000 bills. A portrait of the country’s beloved long-serving post-independence president, Julius Nyerere, graces the 1,000-shilling bill, worth 40 cents. The others make up for lack of value with nice images of wildlife.